By Lou Farrell, Senior Writer, Red Planet Bound

In space exploration, the tiniest mistakes can become mission-ending moments. However, those high-stakes failures represent some of the most valuable data points for space agencies. Every anomaly review, redesign and retest strengthens future missions, turning hard lessons into better hardware and smarter processes. In that sense, progress in the final frontier is a cycle of setbacks, scrutiny and steady space agency improvements rather than a straight line.

Learning from the Tragedy of the Apollo 1 Fire

The Apollo 1 fire was one of the most sobering moments in the history of human spaceflight. During a routine launch rehearsal on January 27, 1967, a flash fire ignited inside the command module, claiming the lives of astronauts Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom, Edward White and Roger Chafee. The spacecraft never left the launchpad, yet the incident immediately exposed how unforgiving spaceflight systems can be, even before a mission begins.

Investigators later determined that several design choices created a chain reaction. The cabin was filled with a pure oxygen atmosphere at high pressure, making even minor sparks catastrophic. An inward-opening hatch with rising internal pressure prevented the crew from escaping in time. Flammable materials inside the cockpit further accelerated the fire. This turned what was a test anomaly into a tragedy within seconds.

In the aftermath, NASA halted crewed missions and undertook a sweeping redesign of the Apollo command module. Engineers replaced flammable materials, reworked wiring and plumbing, introduced a mixed-gas atmosphere for ground testing, and redesigned the hatch. The new doorway became known as the Block II “unified hatch,” an outward-opening design that allowed astronomers to release it more quickly in an emergency.

These changes altered safety standards across human spaceflight and proved essential to the success of later Apollo missions. This case also embedded the lesson that progress in space exploration often comes at a profound human cost, but that learning from failure can ultimately save lives.

Miscalculations on the Path to Mars

Few mission failures demonstrate the unforgiving nature of space exploration more clearly than the loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter in 1999. After a nearly year-long journey to Mars, the spacecraft was expected to slip smoothly into orbit and begin studying the planet’s atmosphere and climate. Instead, it entered the Martian atmosphere at a dangerously low altitude and was lost before it could send a single image back to Earth.

The root cause was deceptively simple — a breakdown in unit conversion. One engineering team used imperial units, while another worked in metric units. The discrepancy went undetected as navigation data was transferred between systems. That small discrepancy grew over time, ultimately placing the spacecraft on a path far closer to Mars than intended. In an environment where margins are already razor-thin, the error proved costly. This mistake resulted in a total of approximately $125 million and decreased public and government support.

In the aftermath, the failure prompted deep scrutiny of how teams communicate, validate data and verify calculations across complex missions. Space agencies strengthened software, standardized unit usage and reinforced cross-team review processes to ensure that assumptions were clearly documented and thoroughly checked.

The loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter became a lasting reminder that precision in space exploration depends just as much on disciplined processes and clear communication as it does on advanced technology.

The Shuttle Era’s Culture of Risk and Renewal

The Shuttle Era was defined by ambition and hard lessons about risk. Two disasters — the Challenger in 1986 and Columbia in 2003 — revealed how complex systems can fail due to human and organizational decisions made under pressure. Together, they exposed the hidden dangers of normalization, where known risks slowly become accepted as tolerable.

The Challenger disaster was traced back to the failure of an O-ring seal in one of the solid rocket boosters, which became brittle due to unusually cold launch conditions. Engineers had raised concerns about launching in low temperatures, but those warnings were overridden amid schedule pressure. The technical failure was catastrophic, but the decision-making process that allowed the launch to proceed proved just as consequential.

Seventeen years later, the loss of Columbia followed a different path but echoed similar themes. During ascent, a piece of insulating foam struck the orbiter’s wing, damaging the thermal protection system. Foam strikes had occurred before without fatal consequences, leading to a culture that downplayed the risk rather than fully interrogating it. When Columbia reentered Earth’s atmosphere, the damage allowed superheated gases to breach the wing, resulting in the vehicle’s destruction.

Both tragedies forced NASA to confront deeper cultural and organizational issues. Beyond engineering fixes, reforms focused on independent safety oversight, clearer channels for dissenting opinions and a renewed emphasis on questioning assumptions. The Shuttle Era served as a reminder that technical excellence must be matched by a culture willing to listen, challenge and pause when something doesn’t feel right.

The Power of Reverse Engineering

When a component fails in space, the problem isn’t always obvious at first glance, and the fix isn’t as simple as swapping in a new part. That’s where reverse engineering becomes so valuable. It lets engineers break a system down after a failure, study how it behaved and pinpoint the weak points that require redesign. Instead of guessing, teams can examine measurements, materials and design details to understand what happened and how to prevent a repeat incident.

In practice, reverse engineering is about clarity, not blame. It helps teams compare what a part was supposed to do to what it actually did under launch vibration, extreme temperature swings, radiation exposure or long mission timelines. Those insights often lead to stronger components, tighter verification processes and better communication across engineering groups because everyone is working from the same evidence.

A classic example is the Hubble Space Telescope, which launched with a primary mirror flaw that caused spherical aberration, resulting in noticeably blurred early images. Astronaut servicing missions corrected the issue by installing hardware that effectively acted like “glasses” for Hubble, including upgraded instruments with built-in optical correction and conducting essential repairs, like replacing gyroscopes to restore stable and precise pointing.

The New “Test, Fly, Fail, Fix” Paradigm for Space Agency Improvements

For decades, space agencies approached missions with extreme caution. It was common to spend years perfecting designs before a single launch. While that method reduced risk, it also slowed innovation. In contrast, a new philosophy has emerged, emphasizing rapid testing, iteration and learning through real-world flight data rather than relying solely on simulations and ground testing.

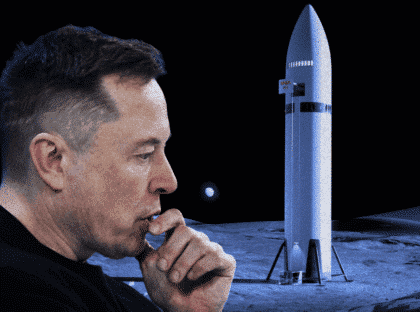

This transition is most visible in the development of SpaceX’s Starship program, where test flights push systems to their limits, often ending in dramatic explosions. Yet, within the industry, they are treated less as disasters and more as data-rich experiments. Each failure provides immediate insight into structural behavior, propulsion performance and system interactions under extreme conditions. This type of information would be difficult or impossible to capture fully on the ground.

The advantage of the “fail fast, learn faster” approach is speed. By accepting controlled failure as part of the development process, engineers can determine weaknesses early, make design adjustments more rapidly and iterate at a faster pace. This mindset has changed how space agencies and private companies think about risk. It proves that failure — when managed correctly — can be one of the most powerful drivers of progress in space exploration.

Space Agency Improvements That Keep Missions Moving Forward

Failures in space exploration are never easy, but they often become the turning point that makes the next mission safer, smarter and more resilient. From redesigned hardware to stronger communication, these lessons compound over time into meaningful improvements for the space agency.

Progress comes from honestly investigating failures and applying the lessons learned from them. In the long run, that cycle of testing, learning and refining is what keeps humanity moving forward in the final frontier.

Author’s Personal Note: Failure is never particularly enjoyable. Wouldn’t it be amazing if everything worked the first time you tried it? But, the critical thing to note is the attitude you hold towards failure. Do you let it break your spirit, or do you let it inspire and invigorate you towards achieving even greater heights?

I hope this article has helped you to see how impactful the latter mindset can be!

Images: NASA/Unsplash